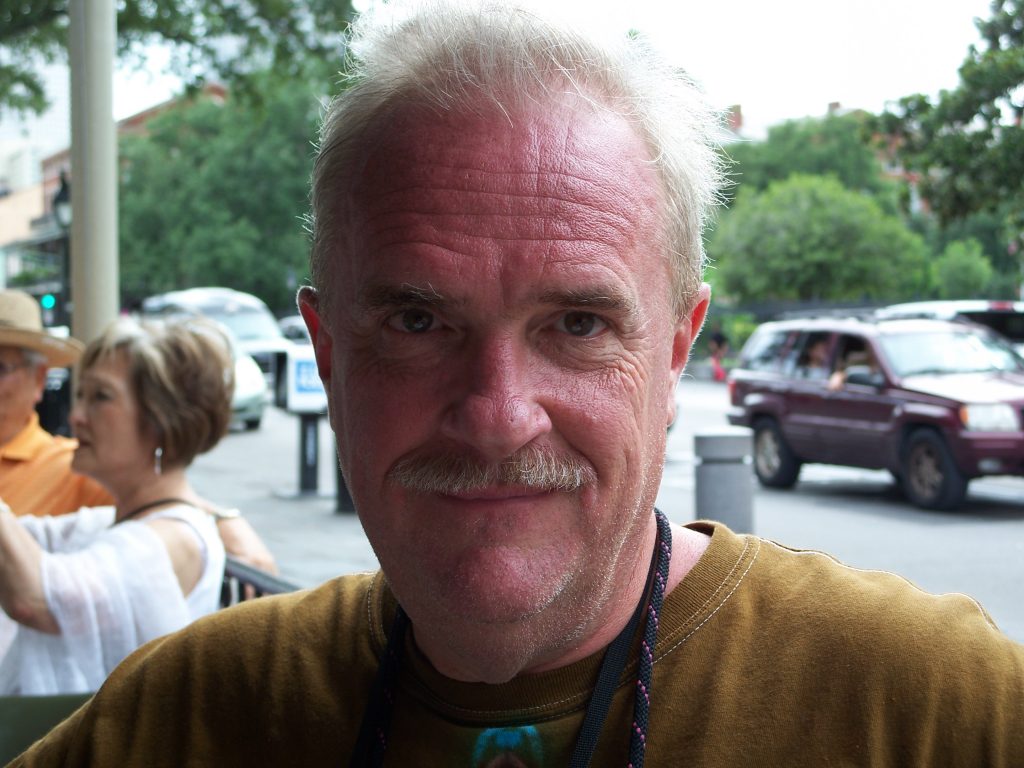

Glenn Steinkamp attended college to become a mapmaker.

He went off the grid to audiotape between 100 and 150 country and rock concerts in his native Missouri. Steinkamp began recording shows in 1984 when he smuggled a small portable tape recorder in Kansas City, Mo. to record T Bone Burnett. He continued to audiotape other concerts including many Grateful Dead shows.

In 1990 he hooked up with videographer John Caspermeyer and they began recording the Skeletons country-rock-soul band, a sonic jewel from Springfield, Mo. Steinkamp had the audio and John handled the video. Once in a while, Steinkamp would bring along a home VCR and later a portable DVD recorder. This enabled Steinkamp and Caspermeyer to have their own video masters.

This subculture is a catalyst for the rare concert footage you see in our 45-minute extra chapter of “The Center of Nowhere” DVD-Blu-ray, edited in chronological order by Jon Sall:

* Morells at the Blue Note in Columbia, Mo. (Sept. 10, 1983)

* Skeletons at Mississippi Nights in St. Louis, Mo. (April 9, 1991)

* Skeletons at Wood House Concert in Clayton, Mo. (Nov. 9, 2007)

* Skeletons at Euclid Records, St. Louis (April 16, 2011)

* Skeletons Reunion Show at Lindberg’s in Springfield, Mo., “Waitin’ For My Gin to Hit Me” only (Sept. 16, 2011).

A warm toast to Steinkamp and Caspermeyer. Band members Lou Whitney, Bobby Lloyd Hicks, and Jim Wunderle are no longer with us, but now I can sit in my living room, crank up the television set and relive the unfiltered joy of one of the most underrated bands in America.

The extras begin with Whitney dealing “30 Days in the Workhouse” in Columbia, Mo. The country song about social justice is Whitney’s loose adaptation of a Leadbelly ballad. Whitney updated the lyrics from the folk-blues master and became a staple of the Morells-Skeletons sets. But they never recorded it.

Eric Ambel covered it on his superb 1998 “Roscoe’s Gang” (Enigma Records) project that was recorded at Whitney’s studio in Springfield with guests Syd Straw, Peter Holsapple, Skid Roper, and others. The song deals with petty thefts like stealing pumpkin pies.

Whitney sings, “I got thirty days in the workhouse, don’t you shed no tears. Cuz’ if I’d been a Black man, they’d give me thirty years.” At the Blue Note, Whitney punctuates the end of the tune by saying, “Think about it.” And this was 1983. Sadly timeless.

The Mississippi Nights segment catches the Skeletons at their zenith. The band’s gang vocals are in full force on Donnie Thompson’s “Outta My Way” (used by Chicago stripper Seka in her early ‘90s performances) and the group is fueled by the double keyboards of Joe Terry and Kelly Brown on a fierce version of Thompson’s power-pop chestnut “Devil in Me.”

For pure fun, there’s the in-store at Euclid Records in St. Louis, Mo. Whitney goofs around with host/music fan Beatle Bob before the Skeletons pay homage to Springfield songwriter Wayne Carson with his Box Tops hit “Soul Deep” and then launch into a spicy version of Junior Walker and the All-Stars “Pucker Up Buttercup.”

In 1990 New York Times pop music critic Jon Pareles raved when the Skeletons headlined Maxwell’s in Hoboken, N.J. (With Dave Alvin as opener.) Pareles wrote in part, “…The Skeletons don’t take themselves seriously, they shrug away rock heroics and undercut romance….But they make every song strut and kick, whether they’re bouncing through bubble gum or twanging and harmonizing on country-rock.”

Steinkamp first saw the Morells in 1980 while living in Kansas City, Mo. “They were such a fun band to hear live,” he said in a recent conversation from his home in St. Louis County, where the Meramec River meets the Mississippi River. “Always a good time live. I saw them at Parody Hall a lot in Kansas City.”

Steinkamp, 62, studied cartography at Southwest Missouri State (now Missouri State) in Springfield, Mo. and then found a job in Kansas City, Mo. “I always liked maps,” he said. “I did cartography for 33 years at the Defense Mapping Agency (at the Aerospace Center) in Kansas City, Mo.. I started out making paper, charts, and maps. We wound up mapping most of the world digitally.” Steinkamp moved to Washington, D.C. for a while and then returned to St. Louis with the agency.

Caspermeyer—who prefers to be under the radar–met Steinkamp through mutual friends. A keen Bob Dylan fan, Caspermeyer had been recording shows since the early 1970s. Caspermeyer shot the 1983 Morells Blue Note video before Steinkamp entered his orbit. Steinkamp also was a radio host/programmer on KDHX-FM in St. Louis between 1989 and 2004. “They had an overnight show on Wednesday,” he recalled. “I’d get there at 3 a.m., play records and then go to work at 6 a.m. I had a vintage country-western show on a Tuesday morning and turned it over to the guy who is still doing it. He does a great job.” Steinkamp also recorded shows from Joe Ely, Los Straitjackets, and the Tail Gators that were later broadcast on KDHX.

Caspermeyer shot the 1983 Morells video before meeting Steinkamp. “He lent it to me,” he said. “It was a nice shot because nobody was standing in the way, no heads to avoid. That’s why I picked that one (for ‘The Center of Nowhere” physical release.). John and I recorded the Skeletons at Mississippi Nights (in 1991) when the Skeletons opened for the Elvis Brothers. Typical deal, we lugged suitcases of our junk down, headphones, did the recording. It took the whole night. We did that a lot back then. John would get more elaborate over time and do more cameras. Sometimes I’d mic the stage. I recorded DAT (Digital Audio Tape) for a while. About ten years ago I got a hard drive recorder. The Skeletons were always very accommodating and very gracious. The club owners were cool as long as we stayed out of the way.”

The archivists captured some great shots, especially of Donnie Thompson’s appointed guitar solos in the Skeletons. “If we were at a festival we’d find a couple of other people to run cameras,” he said. “But when you’re familiar with the music you know where you ought to be. I was mostly concerned with getting a good audio sound. It was a team effort.”

Steinkamp also gave some of his Off Broadway (St. Louis club) concert audio to Skeletons-Morells fan Tom Taber of Albion, N.Y. Taber was as obsessive about this music as I am. He self-produced a series of limited edition live CDs. I bought his “Instant Happy!!! (The Symptoms/Skeletons/Morells Story–102 Songs About Food, Cars, and Drinking)” at Euclid Records in St. Louis in one of my 30 something trips from Chicago to Springfield to work on the documentary. I’m especially sentimental about Disc 4: The Morells at FitzGerald’s in Berwyn, Ill. Sept. 16, 2000, a night that wound down with Ben Vaughn’s “Growin’ a Beard” and Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.”

Steinkamp is proud of capturing the Sept. 16, 2011 reunion show in the Skeletons’ home town of Springfield. The ensemble checks in with a cresting version of Ronnie Self’s “Waitin’ For My Gin To Hit Me.” Besides the core Skeletons, guests include Springfield songwriter-producer Nick Sibley and Springfield rock vocalist Jim Wunderle, best known for his work in the early 1980s Springfield band Dog People. Wunderle would die a year later at the age of 59.

“The reunion show was the grand finale with Donnie,” Steinkamp said. “He maybe played with them one other time after that. (Lou Whitney’s audio engineer) Eric Schuchmann ran the sound for that. I got a nice feed from him. I had a little mixing board, John had a couple of cameras set up. The band got back together with Mark Bilyeu. The band kept going strong.”